Disclaimer: I am not a programmer, so you’ll have to forgive my bad habits and general inefficiency when it comes to programming.

Arduino code is composed of two parts: the setup, which runs once at the beginning, and the loop, which runs over and over again. The setup portion of the Arduino code is very simple, and is mostly setting up pins, interrupts and communications, as well as driving the outputs of the Arduino to a known state. Most of it is trivial, but I will show how I set up the interrupts since I had to do some research for it.

The three buttons are attached to pins A1, A2 and A3. I didn’t want to constantly sample these buttons, so I wanted to use an interrupt to do that. As you can see in the pinout above, A1, A2 and A3 all have PCINT (Pin Change INTerrupt), which means the Arduino will interrupt the code when any of the buttons changes state. To enable the interrupts, you have to enable the interrupt (line 1) and then unmask the pins that can generate an interrupt (lines 2~4). You can read about the relevant registers for this interrupt here.

I wanted to sample the thermocouple at a constant frequency. This cannot easily be achieved using polling, so I needed to set up an interrupt for that too. I decided 25 ms between samples was a good number; fast enough to monitor the data, but not too fast to the point of redundancy. In order to set the interrupt, I had to put the timer in the correct mode (line 3), put the 8 MHz clock through a 1024 divider (lines 4~6), set the threshold to 196 (line 7) and then enable the interrupt. As line 7 shows, 196 is the threshold I used because it gets me a value of about 40 Hz, which will generate an interrupt about every 25 ms. You can read about the relevant registers here.

Within the loop, the architecture is as shown above. I’ll go into the ISR (Interrupt Service Routines) first.

An ISR is exactly what its name says; when an interrupt is triggered, a piece of code is executed to service that interrupt. An important characteristic of ISRs is that they need to be fast; since you’re interrupting a piece of code, you want it to be fast to minimize the impact you’re having on the rest of the system. Therefore, you shouldn’t have print statements or really long function calls. Fortunately, for this project, nothing is super timing critical.

As I mentioned earlier, I didn’t want to poll the buttons; however, I will poll the flag (buttons_flag) that is set when the buttons have changed states. In this ISR, I set the flag and then grab the state of the buttons. Because PINC is a register that has the state of all the pins on port C, and I only care about three of the pins, I mask the data from that register to only look at those three pins.

When the timer interrupt goes off, it is time to get new temperature data from the thermocouple module. I first set the flag to indicate that new data is available, then perform SPI communication to the module to get the data. I put the retrieved data into an array (temp_array) after converting the data from bits to floating point. In order to make the data slightly more stable, I make oven_temp an average of 5 data points. ref_temp is the temperature of the thermocouople module itself (as in the IC), which I only keep track of for logging purposes. What we’re really after here is oven_temp, which is the temperature of the thermocouple located inside of the oven. As I stated earlier, an ISR should be fast, so I’ll move the SPI communication, floating point conversion, and averaging to outside the ISR. However, writing the code this way on the first draft helps me keep it straight in my head.

The UI state machine is the most complex part of the code. It determines what the push buttons do, what to display on the LCD screen, and what the temperature in the oven should be. The state machine starts off in the SELECT state.

When the machine is in the SELECT mode, it displays either “Profile” or “Manual” on the LCD; pressing the left or right buttons will change which of those two is displayed. Pressing the middle button will cause machine to change from SELECT to either PROFILE or MANUAL, depending on what was being displayed on the LCD. The code keeps track of start_time, which is important for calculations later on.

In MANUAL state, the left and right buttons will allow you to adjust the temperature that is displayed on the LCD; pressing the middle button will cause the set temperature to update to the value shown on screen, causing the oven to heat up to that temperature. The temperature can be set from 30 to 300 degrees Celsius. Pressing left when at 30 degrees will show the text “Cancel”, and if you hit the middle mouse button at this point you will go back to the SELECT state.

Here, the left and right buttons don’t do anything, and the middle mouse button allows you to abort the profile. Unlike in MANUAL state, where the set_temp was adjusted manually, in PROFILE state set_temp is calculated based on the inputted profile and the amount of time that has passed. The really long equation that determines the set_temp value is linear interpolation. For example, if the profile is 100 °C at 30 seconds and 200 °C at 90 seconds, then set_temp is 125 °C at 45 seconds, 150 °C at 60 seconds, and 175 °C at 75 seconds.

str1 and str2 are determined in the UI state machine. I initially had the LCD update on every iteration through the loop, but that caused the LCD to flicker very badly; evidently updating causes the screen to clear for an instant, so the constant updating meant constant flickering. Therefore, the LCD only updates if str1 and str2 are different from what was already on the screen. str1 is the first line of the LCD screen, while str2 is the second line (my LCD module is 2 lines of 16 characters, for a total of 32 characters available to display at once).

Here is where the code actually turns the relay on or off. relay_enable is set by the UI state machine; in the SELECT state, the relay is not enabled. In MANUAL, the relay is enabled when the user updates set_temp, and disabled when the user goes back to SELECT state. In PROFILE state, relay is enabled at the beginning and disabled at the end of the profile. This prevents the relay from turning on (or remaining on) by accident. I also added hysteresis to make sure the relay doesn’t flicker on and off rapidly, since that would impact the life of the relay as well as cause current and voltage surges on the heating elements and the relay, which would be bad. For example, if set_temp is 70 °C, then the relay will remain on until the oven temperature exceeds 70 °C, at which point it will turn off. Then, the relay will turn on again when the oven temperature drops below 68 °C. Hysteresis puts (in this case) 2 degrees Celsius between the relay turning on and off.

This would also be the part of the code for implementing a more complex controller. For example, you could implement a PID (Proportional – Integral – Differential) controller here to get better settling time and reduce overshoot. For now, I’ll keep the relay control simple and see if I need a more complex one as I do testing.

Lastly, I use serial communication for debugging purposes. As the Arduino runs, I can see what the oven temperature and set temperature is, and whether or not the relay is on. I can then make sure the code is operating as expected. Note that the serial communication occurs only when the relay is enabled; not much point in monitoring the state of the oven if the relay can’t be turned on. Note that relay enabled does not mean the relay is on; it just means the relay CAN be on.

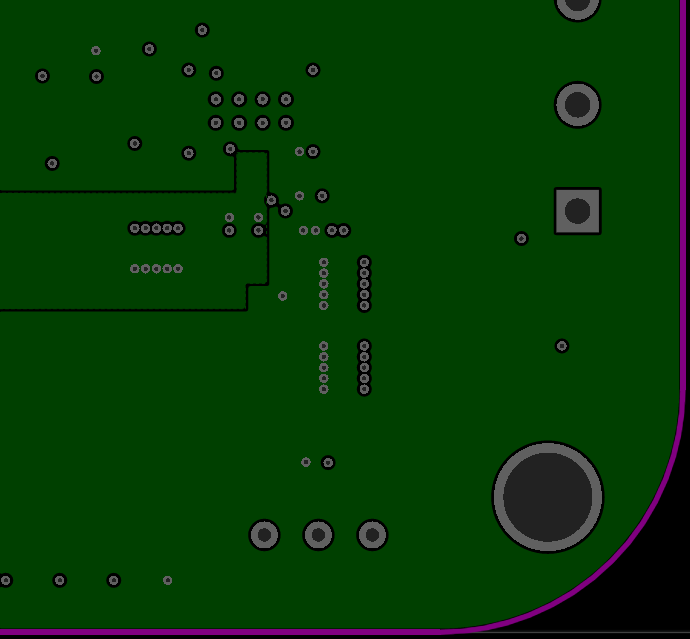

I’ve soldered the Relay Board, and the User Interface Board. Using both, I’ve done some benchtop testing. Now, I’ll have to integrate it into the oven and run a test to see how closely the oven can keep a constant temperature, and how well it can follow a profile.